Aman Gopal Sureka is a Robotic Engineer from Western Michigan University; is the Owner and CEO of the Kolkatta based Manufacturing Automation and Software Solutions but above all he’s the progenitor of Khol Khel, an enterprise that designs and produces tools and games for learning, creativity, and cultural preservation. These tools and games are rooted in the rich traditions of play from across the world–through them Khol Khel aims to create, curate, and promote experiences that foster collaboration, strategic thinking, and social-emotional development.

The Indo-Pacific Politics talked to him about the ancient board games or the ancient chess in India and China in a bid to understand the shared civilization heritage of games and mental cognition. Aman Gopal has revitalized and repackaged the ancient Indian chess called ‘Buddhi Yoga’–it’s available as an app. and can be downloaded here.

IPP: What was original chess like? Who invented it in India, in which year? What was its original purpose?

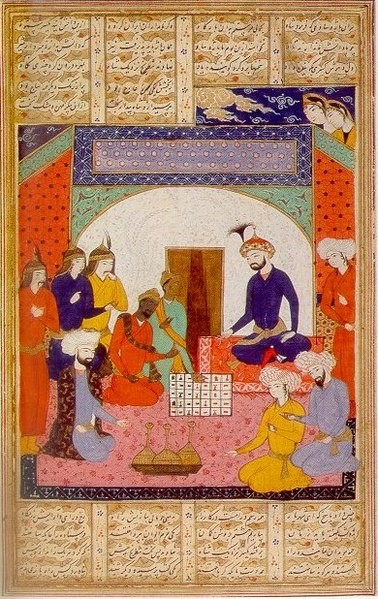

Aman Gopal Surekha: Shatranj and Chaturanga are the predecessors of what we know as chess. Shatranj is possibly the ancient version from which modern chess has evolved. Both the playing platforms were simultaneously popular in India and coexisted as a lifestyle engagement in different parts of India, from Kerala and Tamil Nadu to Rajasthan and Bengal. While “shatranj” was more a game to develop strategy and cognitive skills (a genre I group under the ‘Buddhiyoga’ games), “chaturanga” was a platform to challenge mental fitness. The origin of the two games is debated. While it is largely accepted that Chaturanga is the predecessor of Shatranj, I feel that the two could have (and should have) been developed almost together.

IPP: How did the chess journey from India to China; in which era? Did it retain its Indian form or did it transform? Why did it transform?

Aman Gopal Surekha: India and China have had very similar play engagements. Chess, Kites and Playing cards are some examples of ancient play traditions in both our lands. While Chess is believed to have traveled from India to China, kites and playing cards are believed to have originated in China. However, there are references to kites and flying toys in ancient Tamil literature, which suggest that kites could have also originated in India. Similarly, the use of tamarind seeds and cloth to make playing cards in Bengal, suggests that playing cards may have existed before paper making technology came into India from China. Playing cards only became popular in the West around the 14th century.

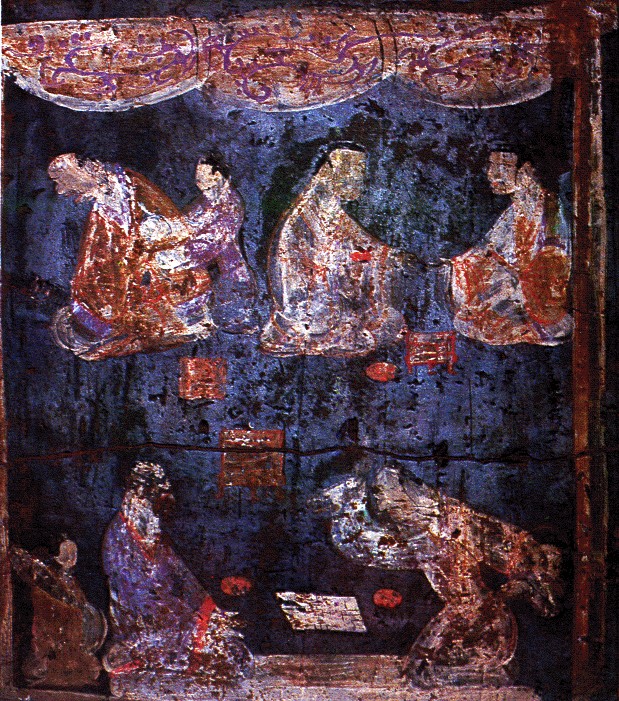

Chinese chess, or Xiangqi, is still very popular in the Chinese community. Modern Xiangqi was already fully developed by the end of the Song dynasty in 1279, whereas chess as it exists now with its modern rules, especially the powerful queen, appeared around 1470.

Early evidence of Xiangqi is very muddled, but there are histories and poems mentioning clearly chaturanga-inspired pieces in Xiangqi games as early as 839 CE. The word “Xiangqi” could plausibly mean “Elephant Game,” “Figure Game,” or “Constellation Game” – which directly alludes to the visible formations of the Chaturanga and Shatranj games. The use of sculpted “figures” and “elephants” which formed an important part of the Indian army are reflected in the adoption of the name. “Xiang” also means where 2 major roads cross – which is similar to “chaupar” or “chaturanga” which means where 4 arms meet.

Those who interpret the characters to mean “Elephant Game” believe that the game evolved from an earlier Indian counterpart, likely influenced upon its arrival in China by the pattern of troops in the Warring States period. Others, primarily Chinese scholars, hold that Xiangqi evolved from a Chinese game called Liubo, an early iteration of backgammon that uses dice. Proponents of such a theory typically believe that the game is a simulation of astronomy, with game pieces mimicking the movements of objects in the night sky. In both these scenarios (the game of backgammon also traces its history to India), the game of Shatranj and the game of Chaturanga (played with dice and stakes) can be seen as predecessors and having deep influence on the playing tradition of Xiangqi. It may also be interesting to note that in the Indian tradition, some of these games were associated with festivals under specific constellations like the “Kaumudhi mahotsav” etc, thus giving another perspective to the association of play and games with astronomy and the night sky.

The game became popular in regions with Chinese influence like Vietnam and Cambodia and possibly Taiwan as well.

(Kaumudi Mahotsav is a very old festival in India, celebrated on the full moon day of Kartik (early October) month with a lot of enthusiasm and joy.)

It is interesting to note that “the language of the nobles” or “mandarin” is inspired by the portuguese referring to the chinese noblemen / bureaucrats as “mandarim”, a portuguese word for bureaucrats, which is in-turn inspired by malay and sanskrit. It is coincidental that the pieces of shatranj (mantrin) also carried a similar name, but the cross cultural exchange and impact of play traditions among the two societies breeds a sense of familiarity and equanimity that spreads a sense of unity and peace.

IPP: What kind of impact did it have on Chinese culture? What is its visible impact on today’s Chinese language, intellect, culture etc?

Aman Gopal Surekha: Anytime a culture adopts a tradition from a different culture, I think a sense of equanimity sets in. I feel there is a sense of “trust” when there is familiarity. One is reminded of the popular saying – “people (families) that play together, stay together”. The fact that these games reinforced local traditions, philosophies and worldviews, while being adopted from foreign lands implies a deep impact and exchange between the two cultures.

IPP: Can you share about why and how you have tried to revive Buddhi Yoga? How’s it relevant even today? Where can the Indian and Taiwanese enthusiasts check it?

Aman Gopal Surekha: I interpret the play tradition of bharat (India) as comprising two broad categories of the games. the Buddhiyoga games which were designed to build mental and cognitive skills and the Buddhi-bala games which were designed to challenge/test the mental fitness of the players. the Buddhiyoga category of board / indoor games can further be classified into different genres. Predator-prey, strategy, race, war, distribution and narrative based games could be some of the many possible classifications. India’s National Education Policy-2020 (revised education policy) has mandated indigenous games and sports to be included into the curriculum and also suggested a list of 75 identified indoor and outdoor engagements in this context. These therefore find immediate relevance in the context of primary education. However, the games are very appropriate for developing social and emotional skills as well. They also align with SEEL [Social, Ethical and Emotional Learning] and CASEL [Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning] frameworks which are recommended by UNESCO and other internationally recognised educational policy and advisory institutions.

The openplay.in website will soon be a wholesome repository for these games, however, for now about 6 different playing kits have been listed on this website.

IPP: Can you share about the other ancient board games you are reviving?

Aman Gopal Surekha: One of the most interesting and evolved playing frameworks from ancient India is the snakes and ladders framework. We have worked on the Rajju-Sarpa (or snakes and ropes) version for many years and are currently in the process of documenting two more versions of the snakes and ladders framework of games from medieval India.

IPP: What are your thoughts on joint endeavors between India and Taiwan on the common knowledge heritage they possess?

We are asking this, being mindful that Taiwan doesn’t own the built heritage sites like China does. But Taiwan does inherit the culture of knowledge which is intangible and needs support to conserve. India and Taiwan share a common intangible knowledge heritage because of the connection between Indian and Chinese civilizations.

Aman Gopal Surekha: I think the legacy of the Buddhist cultural spread from India to China-Japan and South-East-Asia is a very important heritage that must be engaged. These will automatically involve common playing platforms like draughts, checkers (ancient Ashtapada of Bharat) as well as snakes and ladders like Buddhist games of philosophical truths and liberation. We must build heritage centers in each other’s cities where our traditions can be showcased and exchanged. Games and Play are very powerful moderators in bringing two societies closer.